December 31, 1862, was a very special evening for the enslaved Africans. It was the night before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, freeing all the slaves in the Confederate states. I then realized she was carrying her child, wrapped in a quilt, to the Praise House; small places of worship built on plantations during slavery. On the quilt I was inspired to paint many patterns. Patterns and symbols associated with the Underground Railroad Secret Quilt Code such as; North Star: A signal with two messages--one to prepare to escape and the other to follow the North Star to freedom in Canada. North was the direction of traffic on the Underground Railroad. This signal was often used in conjunction with the song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd”, which contains a reference to the Big Dipper constellation. Two of the Big Dipper’s points lead to the North Star. Log Cabin: A symbol in a quilt or that could be drawn on the ground indicating it was necessary to seek shelter or that a person is safe to speak with. Some sources say it indicated a safe house along the Underground Railroad. Flying Geese: A signal to follow the direction of the flying geese as they migrated north in the spring. Most slaves escaped during the spring; along the way, the flying geese could be used as a guide to find water, food and places to rest. The quilt maker had flexibility with this pattern as it could be used in any quilt. It could also be used as a compass where several patterns are used together. Also sewn in the quilt is a piece of the Confederate Flag, representing her soon to be past and the blood, sweat and tears shed; which she and others endured during slavery and oppression. Also, spilling over the edge of the old steel drum top is the United States Flag representing freedom for all. One Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. The quilt futher represents her hopes, dreams and prayers, not only for her child and herself, but for generations to come. The look in her eyes is one of hopefulness yet sorrow, joy and pain. Most of all, her eyes reflect her desires to be free and for the freedom of all of her future generations. I remember the overwhelming emotions that filled my eyes as the Confederate Flag was removed after the murder of nine innocent African Americans in a church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015. Although not nearly as emotionally moving as it may have been for her on New Year's Eve in 1862, after being enslaved most of her life and witnessing and experiencing the suffering, torture and killing of so many, I understood and experienced just a glimpse of her emotions. Suddenly it dawned on me, that this New Year's Eve will be the first time in my generation that, that same flag; which represented slavery and oppression to her, will not be flown over the Capitol of South Carolina. It was put up 54 years ago to protest the Civil Rights Movement and was never removed until 2015. Her prayers of FREEDOM were answered. So, I named this piece, 'Amazing Grace.' "South Carolina taking down the confederate flag - a signal of good will and healing, and a meaningful step towards a better future." - President Barack Obama

0 Comments

I'm a strong believer that every piece of art that God inspires me to create, He already has someone predestined for it. It's just a matter of the person finding their piece. I created this piece entitled, 'Rejoicing' on an old piece of tin I found here in South Carolina. As I was leaving for Washington D.C., this piece of tin spoke to me and was ready to reveal the story which was within it. She emerged after my visit to Georgetown in D.C. She was rejoicing because she made it North to freedom! In the late 18th century and 19th century African Americans comprised a substantial portion of Georgetown's population. She was now a testament of freedom along with the African-American history that remains today at the Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Georgetown, which is the oldest African-American congregation in Washington.

Months later a lady saw an ad in a newspaper in Columbia showcasing my art exhibit. She and a friend came to my exhibit a few days before it opened and I just happened to be there delivering my work. She came in with striking red hair and green eyes; the same charateristics as another painting in the exhibit, which I call 'Cotton'. So, immediately that became her nickname. In hand was the image she had clipped out of the paper. She said when she saw it in the paper, she had to find me. She and her friend started observing my art. Then suddenly she saw 'Praising' and right away she said, "She speaks to me and I want her." Her friend also found a piece that spoke to her as well. It was not until recently that Chris, whom I call Cotton, discovered and read more about the piece'Praising' finding her way to freedom. Chris then wrote these words to me. "I found Praising , never knew that it also meant she made it North. Maybe I felt such a connection because I also made it back to freedom without getting killed during World War II and free from German occupation where we were treated like slaves or worse." - Chris She not only felt the connection to this piece spiritually, but also the understanding of her struggle. 'Rejoicing' found her home with Chris and everyday she is a reminder of gratefulness and joy in her home. She symbolizes what they both understand, 'Freedom.'

Helping to develop the Forgotten Communities Project as a part of the National Cultural Heritage Initiative is one of my reflections and also apart of my purpose. I not only believe God gave me art to encourage and inspire others, but also to help rebuild communities through the arts. Like the woman in this piece, my work is not done. There are many people to encourage and inspire and many cities to help rebuild through art. Here is just one of my reflections....  Yesterday I delivered artwork for my 'From Whence I Came Exhibit' to the Arthur Rose Museum of Art at Claflin University, Orangeburg, S.C. Claflin University, founded in 1869, is the oldest historically black university in South Carolina. 'From Whence I Came Art Exhibit' is a reflection of the spiritual journey of people of African Descent through my art. It is a glimpse into their culture, their heritage and their traditions. This exhibit captures the movement of a people from the Door of No Return, which was the last door the Africans went through before getting on to the slave ships, to Freedom’s Door-walking into a new way of life, while struggling to preserve their identity, customs and traditions in a new world. When I arrived, I was greeted with a warm welcome at the door and when I stepped inside I was overwhelmed by the beauty and energy from this museum. The museum is dedicated in the memory of Artist Arthur Rose Sr., known as Dean of Black Art in South Carolina. I could literally feel the kind creative spirit that dwells within the walls of this museum. After reading about Arthur Rose Sr., my recent paintings 'I Am A Man' and 'Aint I A Woman' spoke deeper to my heart. Painted on fencing, they symbolize one's ability to step pass the boundaries inwhich this world and even ourselves have placed on us. I began to remember an exhibit I once saw years ago.. In it was a black and white photograph of a little girl from Charleston. She was standing behind an iron gate. One side of the gate was open and the other was closed. In the distance you could see a large plantation house behind her. She stood there, face pressed against the fence, as if she was locked in the state she was in; afraid and unabled to take one step over and one step out. Her freedom was literally steps away, but it's not until she has a renewing of her mind and a desire in her heart to be free, that she will step out and live out her destiny. Arthur Rose Sr. was one who I believe lived out his destiny. A South Carolinian by birth, Arthur Rose spent his entire career as an artist and educator in his native state, where he worked to overcome barriers confronting African American artists. Born in Charleston in 1921, Rose was one of eight siblings to attend local public schools and the only sibling to pursue higher education. Following a brief stint in the Navy during World War II, Rose graduated from high school and enrolled in Claflin University in Orangeburg, South Carolina in 1946. After earning a bachelor’s degree in 1950, Rose temporarily relocated to New York, where he pursued advanced studies under the guidance of Hale Woodruff, among other notable faculty, at New York University. During his two-year New York sojourn, Rose’s Southern home was never far from his mind. Indeed, Charleston was a significant source of inspiration. Rose described the rolling sea and fluttering breezes of the Carolina Lowcountry—those natural elements constantly in motion—as influential to the development of his organic creative process, in which the final composition asserts itself, rather than having been preconceived. Known for his expressionistic sculptures, Rose nonetheless insisted that he was a painter first. His naïve figural and genre scenes are populated with subjects inspired by African folklore—from lithe gazelles to praying parsons and harlequin poets. Critics and scholars have described Rose’s graceful, sometimes humorous, forms as owning a light-hearted vitality indicative of the artist’s own carefree nature. Upon completing his graduate degree in 1952, Rose returned to Orangeburg to begin a thirty-one year tenure at Claflin University. There, he served as chair of the art department and, following an eight-year leave of absence during which he was artist in residence at Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina, returned to Claflin as an associate professor of art. At Claflin University—the only college in the South where African Americans could earn a bachelor’s degree in art at mid-century—Rose went to great lengths to exhibit his students’ work. Because segregation limited their access to commercial galleries, Rose initiated an annual “Fence Exhibit,” in which students publically displayed their art along the front fence of Claflin. Though he retired from teaching in 1991, his enthusiastic efforts to create opportunities for his students, are not forgotten. In fact, many successful African American artists of the state, such as Leo Twiggs, continue to refer to Rose as “the Dean of Black Arts in South Carolina.” In 2005, ten years after the artist’s death, Claflin University renamed their newly renovated gallery space for faculty and student exhibitions the Arthur Rose Museum. The following quote appeared in the program for the museum’s dedication: “Mr. Rose created an atmosphere in his studio/classroom that reminded one of the movement of the winds and waves that he experienced as a child in Charleston: the reassuring notion that natural activity was always occurring.” His motto for a successful future is "Never let hard work or criticism impair your progress. Take them as a challenge and master our dreams." As he himself did, Rose urged young people to "pursue your vision to the fullest." It's an honor to exhibit my artwork here at the Arthur Rose Museum of Art at Claflin University. "Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour. - Romans 13:7

Blackberries have multiple meanings across religious, ethnic and mythological realms. They have been used in Christian art to symbolize spiritual neglect or ignorance. Blackberries originally grew wild in fields, on hillsides and along woodland edges. Unmanaged and untended, the trailing vines wrapped themselves around whatever they came into contact with as well as with one another, often creating impenetrable thickets that made most of the fruit hard to get at. At best, only the berries growing on the outermost vines could be harvested and the rest were left to rot or serve as food for whatever wild creature was able to get at them.

America's Reconstruction :the Untold Story is much like blackberries. “Reconstruction is known for the federal government’s attempts to grant equal rights to former slaves as well as the political leadership of African-Americans in the former Confederate States,” says Dr. Morris. “Reconstruction actually began in Beaufort County in 1861, the first year of the war, and, though the era fell short of many Americans’ expectations, it laid much of the groundwork for the ‘Second Reconstruction,’ or the Civil Rights Movement, of the 20th century.” On November 7, 1861 (long remembered by former slaves as the “day of the big gun-shoot”), just months after the fall of Fort Sumter, the Union Navy recaptured Port Royal, South Carolina. This prompted the panic and mass exodus of the region’s plantation owners, who left behind thousands of their slaves. This provided an opportunity for a dress rehearsal of sorts for Reconstruction known as the “Port Royal Experiment.” Northern strategists saw the newly freed people of the Sea Islands as an ideal test group for experiments in education, citizenship, and land ownership for potential implementation after the war. The experience there prepared participants and observers for the more widespread, future implementation of truly revolutionary changes in education policy, civil rights, and democracy, and importantly showed that these policies could succeed in longer-range plans for the reconstruction of the South once the war could be brought to an end. Sandwiched as it is between the dramas of the Civil War and the Jim Crow era, Reconstruction suffers as one of the most understudied and misunderstood periods in American history. Part of this misunderstanding is due to the history’s complexity—scholars’ interpretations of the period have ranged from 12 years of abject failure where unprepared, vengeful, and corrupt former slaves nearly ruined the South and a period of excessive punishment of the defeated former Confederacy by the victorious North, or, alternatively, as a bright age of hope that ultimately failed, but only insofar as it did not go far enough or achieve its lofty goals. Recently, scholars have agreed with W.E.B. Dubois’ conclusion in his 1913 study Black Reconstruction in America that its overthrow was a tragedy, a “splendid failure,” whose revolutionary agenda could not overcome the overwhelming forces set against it. http://www.uscb.edu/americasreconstruction/ The first night of the Reconstruction Institute at USCB, this tall regal stature of a man, Dr. Emory Campbell, came to the podium to speak. He began to tell a story of the gullah people who were being used for this experimental time of America's Reconstruction. He spoke of the children of Historic Penn School, one of the first school for blacks in the South, and how they would ever so often just leave class and go pick blackberries. When I heard that story my painting "Pickin' Blackberries' came to mind. I then asked the Lord, "Does this little girl picking blackberries represent the spiritual neglect and ignorance of Recontruction? Does she understand that she was, at that very moment, going through a bright age of hope?' He simply answered, "She represents that you are where you're supposed to be, at the moment you're supposed to be in time, doing exactly what I created you to do, painting what I'm inspiring you to paint. " 'According as he hath chosen us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and without blame before him in love: Having predestinated us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself, according to the good pleasure of his will.'-Ephesians 1:4-5

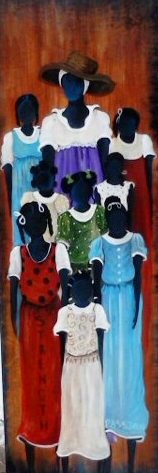

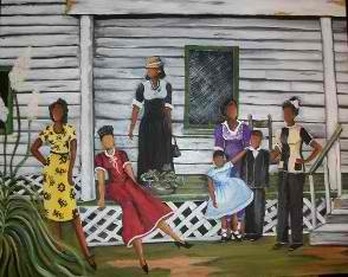

Reading the history of Emanuel AME known as 'Mother Emanuel' the meaning of my painting 'Me and My Chillun'' became clear. Mother Emanuel was formed by both free and enslaved blacks. The church was burned to the ground in 1822 after the arrest of Denmark Vesey's planning of a slave revolt. in 1834 its doors were closed due to a law prohibiting African Americans from worshipping without white overseers and consequently had to worship in secret throughout the Civil War. The church building was severely damaged in the earthquake of 1886 and had to be rebuilt in its current form in 1891.

You can now also view and purchase my artwork in Downtown Beaufort, South Carolina at Scout Southern Market.

Scout Southern Market, recently featured in South Magazine, specializes in products that capture the spirit of the contemporary southern lifestyle. Sourced from across the great southern states, they carry unique home décor, furniture, lighting, jewelry, gifts and small-batch specialty foods that appeal to both local and out-of-town guests looking to bring home a piece of southern style. So stop by Scout Southern Market and view my new piece entitled, 'Preparation.'

http://www.scoutsouthernmarket.com/

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed